Blog

Working in memoir requires a writer to stand in the fire of truth. This means holding ourselves accountable to seeing what’s true about our lives. Part of my process as a book writing coach is to point clients to ways they can write with a more open heart. Writing well about our life requires us to open our hearts. When one’s heart is open, we bring full awareness and presence to all situations and people. We are capable of writing patiently and honestly about the heartbreak and the ecstasy, as well as the ordinary. We can face the whole catastrophe of being alive, as Zorba might say. And we can do so from a place of wonder and generosity instead of from blame and shame.

Here’s an amazing thing about the human heart: you don’t need a field guide to learn how to open it. Yes, meditation, yoga, and other spiritual practice can help us slow down and develop distance, open space, between what happens to us and how we respond to the challenges. But, if you let it, life will open your heart for you. If, at first it doesn’t happen, rest assured that life will give you a second chance.

Years ago, I came down with pneumonia and was bed-bound. It was a dark time. Breathing was hard, and I was exhausted all the time. My lungs felt leaden, and I couldn’t seem to fill them with enough air. Worse, I was living with some heavy emotional baggage, too. I was grieving the recent death of my mother, and I was heartbroken after a breakup of a relationship I’d been hopeful about. Thanks to antibiotics, I wasn’t in danger of dying, but I sure felt like I might. Merely walking down the hall from bed to kitchen left me gasping. Taking a walk up the street was out of the question. The six-week illness was one of the loneliest times of my life-and looking back, it changed me in an important way.

During one of the darkest nights when I felt panicked and alone, I set Spotify to the chanting of Krishna Das, an American purveyor of Indian devotional music. His deep baritone sends vibrations deep into my chest cavity. His chanting in Sanskrit takes me to a place inside me that isn’t part of the physical world. This place, if you can call it that, feels immense, sacred. When I go there, I don’t feel anxious. I feel safe.

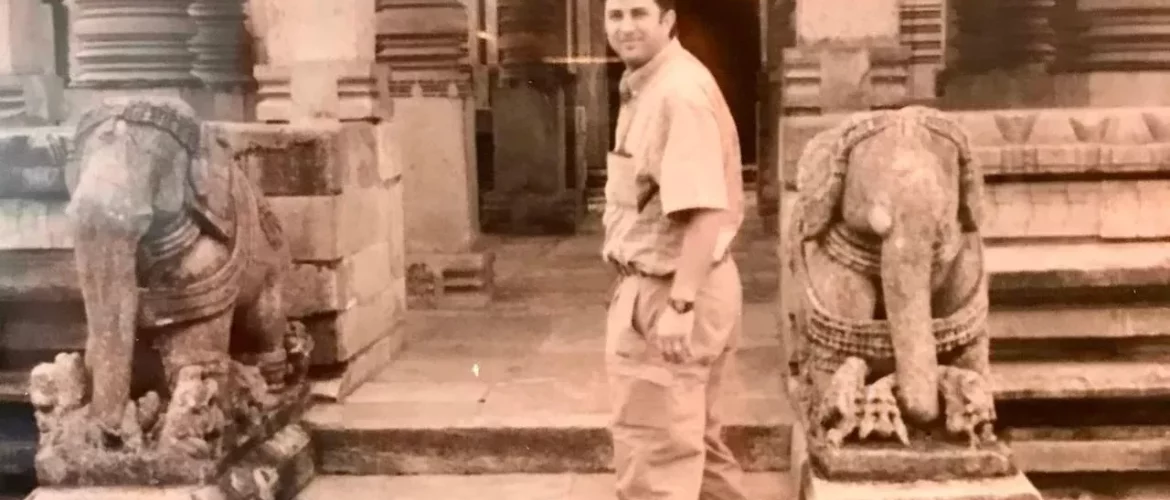

One night, as I lay in bed, listening to “ Sri Argala Stotram (Show Me Love),” a sung prayer to the Mother Goddess, I began to reminisce about a reporting trip to India in 1999, a decade earlier. I was 33, and traveling in Asia on assignment for Wired magazine. After finishing my reporting work in Bangalore, I’d flown to Varanasi, one of the oldest cities in the world, a place so holy that devout Hindus go there to die. I wanted to see this place. I wanted to feel the sacredness for myself.

On my first morning in Varanasi, I descended the great stairs to the Ganges and hired a boatman to take me upriver to the burning ghats, where bodies are brought for cremation. I stood on a high platform, shrouded in smoke. I silently watched the body of a young Indian woman being brought into the fire area and lain on the intense, open-air blaze. Too young to die, I remember thinking, as her silky black hair was consumed by fire.

Fueled by fever and aloneness, the mental images were as vivid as life. I remembered the younger man I was, and how confused I’d felt watching the woman’s body burn. Though I’d always known myself to be very empathic, almost to a fault, I couldn’t muster a single feeling of sadness during the cremation. I tried again to connect with a feeling that might be considered appropriate for the circumstances. Nothing. And then I figured out why. The pills I took back then for recurrent depression were blocking my feelings. I was completely numbed out. I’m not talking about a few pills. During the 1990s, under doctor’s orders, I took twelve different medications, a total of 22 pills per day. How this happened, I’m not sure, except that every time I visited the doctor, he added more pills to my regimen, and never took any pills away. Eventually, the medications became a bigger problem than depression. Their side effects blunted my spirit and stole my intellect. I couldn’t speak without slurring. I couldn’t walk without stumbling. Worse, I couldn’t feel my own heart. You would think I could have noticed this before India. I guess I was sort of aware of the toll the pills were taking. But it took this heightened moment of witnessing the cremation on the banks of the Ganges to really see how compromised I was. It was years ago now, but it remains a difficult, confusing time to even consider. As I write this, I am filled with grief and anger. Anger at the doctor who prescribed this chemical cocktail. Anger at myself for taking them. Grief at the seven lost years that I’ll never get back.

Halfway into the Krishna Das song, the Sanskrit chanting ends and he croons in English: “I wanna know what love is./I want you to show me.” That’s right! The sacred chant turns into the cheesy 1970s rock ballad by Foreigner. The sacred and the profane become one.

I knew all about how Krishna Das became a kirtan singer. In 1970, Krishna Das’ name was Jeffrey Kagel. He was the lead singer in a successful rock band when he met and became enthralled with Ram Dass, née Richard Alpert, a former Harvard psychology professor who’d been fired along with his partner, Timothy Leary, for introducing students to LSD and doing psychology experiments that strongly resembled parties. Ram Dass had spent months at an ashram in the Himalayan foothills of northern India, at the foot of Neem Karoli Baba, a yogi and guru who taught that nothing else mattered but love. This guru changed Jeffrey Kagel’s life and rechristened him Krishna Das. The key to happiness was not fixing yourself, the guru taught, it was simply learning to be love. Soon Krishna Das was living in India, walking around in a maroon one-piece dress living as an ascetic holy man. I was fascinated by these stories. Being love. Is that possible?

Love had long been a mystery to me, as it is to most people I know. Growing up, I’d observed my parents’ struggles with love. I left my childhood home confused; no, baffled. As I listened to Krishna Das sing on that dark night of the soul, I realized that love has been my lifelong obsession. I don’t give my parents all the credit-I’ve had plenty of my own struggles related to love, including two marriages, two divorces, and several shorter-term relationships. I left them all confused. What was love? Suddenly, I understood why Krishna Das tacked the Foreigner song to the end of his chant about love. “I wanna know what love is. I want you to show me.” Love is a mystery to most of us. I didn’t realize then, but Krishna Das was exposing me to Bhakti yoga, the yoga of devotion, chanting, and love. His love guru was actually coming through my phone. Today, Krishna Das claims, “My guru taught me everything I know about real love. Guru loved me from the inside. When you’re exposed to that, it’s transforming. We’re used to affection being handed out when we’re good little boys and girls. When we smile and laugh and do the right things. But this is very different from that.”

In other words, real love is self-love. Period.

People believe in much stranger things. Seriously.

Of course, I healed from pneumonia, and, with the passage of time, I worked through the grieving process of losing my mother. Eventually, I returned to India, and I traveled by train to Kainchi where I visited the ashram of now deceased Neem Karoli Baba. For good reason, Americans are doubtful, even fearful, of spiritual gurus; examples of gurus taking advantage of people are everywhere. But many of the men and women who spent time with Neem Karoli Baba say he was legit. They were changed in his presence. His other famous disciples include Lama Surya Das, a New York-born teacher of Tibetan Buddhism, Daniel Goleman (mindfulness expert and author of Emotional Intelligence), Larry Brilliant (epidemiologist, tech CEO, philanthropist, author), Rameshwar Das (author). After the guru’s death, many other leading American businessmen caught the Maharaji bug, including Steve Jobs and Mark Zuckerberg, both of whom went on pilgrimages to Maharaji’s Kainchi ashram. This small man had a big impact on American spiritual and business culture. These students came home and became important thought leaders in business and spirituality. With 40 million Americans practicing asana (yoga poses) at home and in studios, the impact is clear.

“For virtually all of these people, being with Maharaji was the single most important thing that happened in their lives,” meditation teacher Sharon Salzburg has said. “I don’t know too many in that community who look back and say, ‘nah, it was nice enough but I was young and foolish.’ It remains totally essential to the core of their being. It’s quite remarkable.”

Though the earthly form of Neem Karoli Baba is long gone, I swear I felt something while visiting the ashram located on a gurgling stream in a scenic Himalayan valley. Maybe it was my imagination. But being in the same place where this guru lived and taught, and where Ram Dass, Krishna Das, and others received his loving presence and wisdom teachings, affected me profoundly. Again, I’m not claiming that I was visited by the guru’s spirit, but then again, who really knows? I’ve come to believe this Universe is far more mysterious than we give it credit for being. While there, in their old stomping grounds, I gained a deeper understanding and appreciation of the path of Bhakti yoga. Bhakti scriptures teaches that we all have access to unconditional love, a type of love that isn’t transactional. This unconditional love already resides in all of us. We simply have to remember that we already are love. In more modern terms, Bhakti yoga is about learning how to love oneself. A lot is written about that topic, and what’s written can feel glib and meaningless. But I think Neem Karoli Baba and other Bhakti practitioners are right. Underneath the conditioning that created our complicated personalities, there is a place inside us all where unconditional love resides. Practices such as yoga, chanting, and journaling, when performed regularly, are useful tools that can take us there.

What practices help you with self-care and self-love? How do you stay present and open-hearted to all that life shows us? If you’re interested in developing a meditative journaling practice, I’d love to help you. In addition to book writing coaching, I teach various forms of journaling that, when done regularly, really can open your heart to new ways of seeing yourself and being in the world. I swear, you don’t have to suffer through pneumonia to develop more awareness and presence. But then again, looking back, that difficult time really was a gift that keeps on giving long after the fever has gone.

— — –

A former senior editor and contributing writer at Outside magazine, Brad Wetzler is an author, journalist, travel writer, book writing coach, and yoga instructor. His book, Real Mosquitoes Don’t Eat Meat, was published by W.W. Norton. His nonfiction writing has appeared in The New York Times Magazine and Book Review, GQ, Wired, Men’s Journal, National Geographic, George, Travel + Leisure, Thrive Global, and Outside. He coaches up-and-coming authors to write and successfully publish their books.